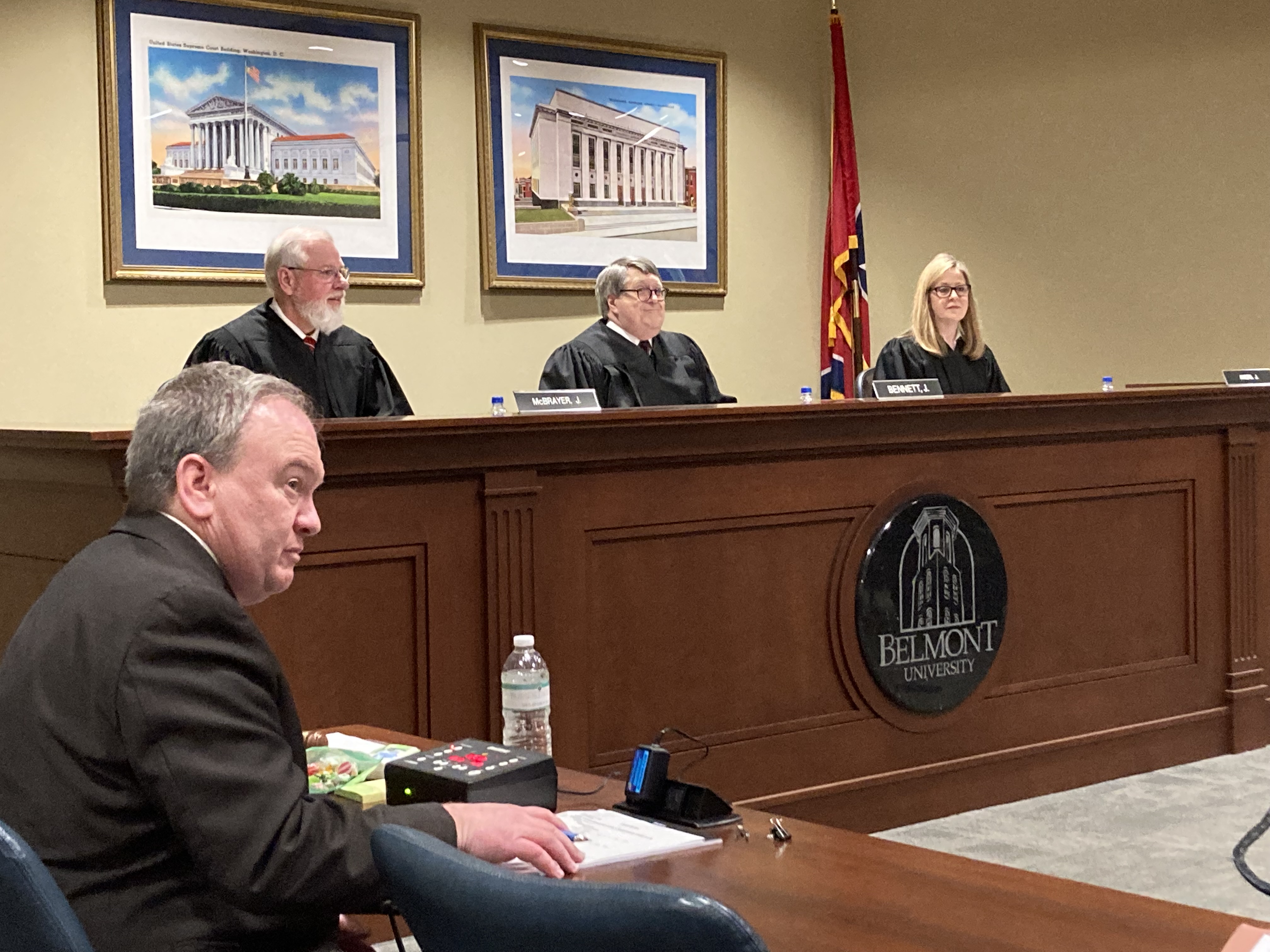

The Court of Appeals in-person oral arguments came full circle on March 11, by returning to Belmont University Law School. The previous in-person session was held on campus just over two years ago, March 4, 2020. Soon after, the Covid-19 pandemic forced the courts to transition to a virtual format.

“We’re back where it all ended two years ago,” said Court of Appeals Judge Neal McBrayer. “It’s amazing to see the transformation that has happened to the Tennessee Courts since 2020. Who would have thought all of this was possible? We now have the technology that allows us to do that. It’s an amazing transformation that’s taken place in a short amount of time, in an institution that’s typically resistant to change.”

Judge McBrayer joined Court of Appeals Judge Andy Bennett and Court of Criminal Appeals Judge Jill Ayers, who filled in for the day. Her introduction drew laughter from the crowd.

“I graduated from Belmont undergrad in 1989 and at that time there was no law school here,” Judge Ayers said. “It’s a great honor and privilege to be here. If you saw a tall guy in a quarter zip that’s actually my husband, who coaches basketball here. There are a lot of Belmont connections in my family.”

Belmont Law School Professor Jeffrey Usman praised the event as a wonderful opportunity for his students to see the Tennessee Court of Appeals in action.

“The audience that you have before you today, most of them, are first year law students in the midst of drafting their first appellate brief,” Professor Usman said. “They are in the midst of preparing for their first appellate argument and so you have an audience that is going to be particularly rapt for learning exactly what they should be doing and how to do this well.”

Following oral arguments, the judges entertained a lengthy question and answer session. Professor Usman asked, “Is there a line between the dramatic telling of facts and the more subdued version? How should attorneys approach writing the fact portion of the brief with regard to that? Should it be a page turner that you’re flipping through?”

“I don’t think I’ve ever read a page turner,” Judge Bennett said. “I prefer facts to be laid out in a straightforward manner. I can tell when you’re shifting a little or you’re twisting it. You may have a different point of view and you want to get that in. I understand that and I expect it, but I don’t necessarily respect it. The argument goes in the argument section, where you take those facts and you make your argument. The fact section, in my mind, is supposed to be just the facts. Not slanted, not twisted with little pieces of argument thrown in.”

The students, who learned that the universal pet peeve of judges are attorneys who click their pens during oral arguments, asked the following questions.

“Is there anything in briefings you don’t want to see from attorneys?”

“I oftentimes read briefs that go into too much detail in the statement of the case,” Judge McBrayer said. “I don’t need to know how many times a trial was continued. I don’t need to know about the motions that were heard and denied, necessarily, depending on the issues before us. That’s the place where attorneys can sometimes go on a little long. I admire the attorneys who can write with brevity.”

“How much does the oral argument actually influence the decision making?”

“I do think a really effective oral argument can change our mind on a lot of those thoughts or maybe there’s an issue we hadn’t thought about as much until somebody brings it out,” Judge Ayers said. “So, I think it’s important for oral argument to give your best shot because sometimes it can make a difference.”

“Is there a sweet spot in between legalese, using language that is complicated, Latin terminology, but then on the other end we shouldn’t be informal? Is there a sweet spot where our writing is most effective when you’re reading it?”

“I’m a big plain language person,” Judge McBrayer said. “I do not like ‘assuming arguendo.’ I don’t use that in conversation and I do not use that in opinions. We don’t speak Latin; it’s a dead language. I don’t like looking up Latin words when I’m reading a brief. There is a caveat there. See what I did with that? There are some legal phrases that can’t be described in ordinary, plain language without taking up a lot of space. The classic example is ‘res ipsa loquitur.’ That is a hard concept to communicate without using Latin.”

“What’s your best advice for new attorneys?”

“The people of the courthouse, the court officers, are the people you need at the end of the day to get your job done,” Judge Ayers said. “Just be nice to those people. It is not hard to just be friendly, and you are no better than they are. In a trial setting I would say, ‘We are all on the same team in that we are trying to get this case tried fairly and impartially, without errors, so it stands up on appeal. You do what you have to do for your client, but let’s all work together and not be jerks.’”

“There are many options for people with a law degree,” Judge Bennett said. “Not everyone is made to be a trial attorney, or go to work for a large law firm, or work in private practice. Don’t sit there and think, ‘I have to do a certain route or I’m a failure.’ You’re not a failure if you get into something you like, you do it well and you take pride in it. Keep your options open, think about what your strengths are, think about what you like and, unless you’re desperate, don’t just take a job because it’s offered. Take it because you want it.”

The Court of Appeals heard oral arguments for two cases at Belmont Law School. The exercise serves as a learning tool for students, as well as an opportunity for judges to share their wisdom outside of the courtroom.